Upcoming newsletter does a review of protective underwear

Dismantling the Culture of Ambivalence: Reframing Prostate Cancer Awareness and Access

Prostate cancer remains a major cause of death among men, yet participation in preventive care is shaped by structural, cultural, and policy barriers rather than individual choice alone. This report finds that inconsistent screening mandates, cultural norms, and burdensome clinical guidelines may contribute to delayed diagnoses and hinder progress in reducing mortality.

9/13/202514 min read

An Analysis of Factors Influencing Men's Engagement with Prostate Cancer Care

Author: Anton João-Luiz Allensworth, M.Ed.

Abstract

Background: Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death among men in the United States. Despite the significant public health impact, men's engagement with preventive care remains a challenge. This report analyzes the hypothesis that men's limited participation is not solely a matter of personal choice, but a complex issue shaped by structural, cultural, and clinical factors.

Objective: This report provides a multi-faceted analysis of the structural, cultural, and policy determinants that influence men's participation in preventive prostate cancer care. It examines existing health infrastructure and policy frameworks, including those for women's health, to understand potential differences in access and normalization of care.

Methods: The analysis synthesizes epidemiological data from federal sources, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. It examines federal legislation, specifically the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), alongside state-level statutory frameworks, using Ohio as a case study. Additionally, the report examens recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the differential public and professional responses to guidelines concerning breast and prostate cancer screening.

Findings: The analysis identifies notable policy differences in federal and state mandates for preventive screening, where comprehensive, no-cost provisions for women's health are not consistently mirrored by similar legislation for men. This policy environment may reinforce cultural norms of stoicism and self-reliance, which, when combined with problematic clinical guidelines, can place a significant burden of "shared decision-making" on men who may be unprepared to navigate it. A consequence of these factors may be an increase in late-stage diagnoses and a potential slowing of the decline in mortality.

Conclusion: A meaningful reduction in prostate cancer mortality may require a fundamental paradigm shift away from a risk-based, discretionary model of care toward a more universal, and proactively offered system. This approach should be supported by public policy and provider practices that address the deep-seated structural and cultural barriers to men's health engagement.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 The Public Health Impact of Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer represents a significant and under-addressed public health challenge in the United States. It is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer among men and is projected to be the second leading cause of cancer death, with an estimated 35,770 deaths in 2025 (American Cancer Society 2024 1). This stands in stark contrast to the high five-year relative survival rate of nearly 100% for localized and regional-stage prostate cancer, a rate that drops to a critical 37.9% when the disease is diagnosed at a distant, metastatic stage (CDC 2023 2). This dramatic disparity underscores the paramount importance of early detection. Despite advances in therapeutics, a decline in the prostate cancer death rate, which fell by half from 1993 to 2022, has recently slowed, a concerning trend that may reflect a rise in diagnoses at advanced stages and signals a critical public health challenge that require a re-evaluation of current practices and policies (American Cancer Society 2024 1).

1.2 Factors Influencing Engagement with Preventive Care

A closer examination reveals that men's engagement with prostate cancer prevention may not be a matter of choice, but rather a response to a healthcare system that is not fully aligned with their needs. This report posits that the issue is rooted in an interconnected web of systemic factors, including policy gaps in legislative mandates, ingrained cultural norms, and professional guidance that collectively create an environment of uncertainty rather than one of empowerment.

1.3 A Roadmap for Analysis

This report deconstructs these factors by proceeding from a foundational clinical-epidemiological analysis to a discussion of cultural and socioeconomic barriers, a deep dive into legislative differences, and a final critique of the impact of professional guidelines. The analysis will demonstrate that effective interventions cannot be limited to simple "awareness" campaigns. Instead, they must address the fundamental structural and cultural obstacles that currently inhibit men's proactive engagement with their health.

2.0 The Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer: The Role of Screening

2.1 Incidence and Mortality in Context

The data on prostate cancer underscores the importance of early detection. As noted, the five-year relative survival rate for localized and regional-stage prostate cancer is nearly 100%, but it plummets to 37.9% for distant-stage disease, highlighting the life-saving potential of timely diagnosis (CDC 2023 2). While screening for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has been a subject of controversy, its widespread use in the early 1990s is believed to have played a significant role in the subsequent halving of the prostate cancer death rate over the next two decades (American Cancer Society 2024 1).

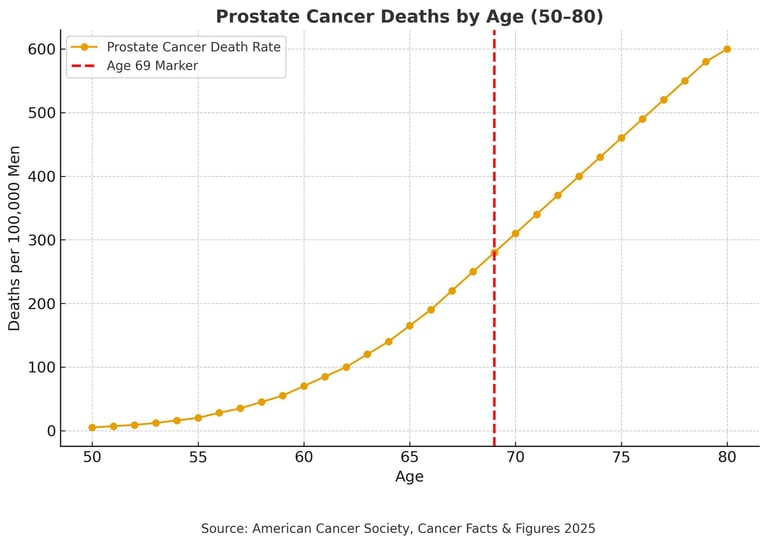

2.2 Age-Related Risk and Screening Guidelines

A central issue with current guidelines is the recommendation to cease PSA testing at an age when the trajectory of mortality is highest. Federal data confirm that prostate cancer risk rises significantly with age. For instance, the CDC notes that from 2001 to 2021, the incidence rate was highest among men aged 70 and older, with a rate of 586 per 100,000 males, and that 42% of all cases occurred in this age group (CDC 2021 3). Consistent with this finding, data from Cancer Research UK show that incidence rates are highest in men aged 75 to 79, with over 17% of all new cases diagnosed in this age group (Cancer Research UK 2017-2019 4).

The following table, which visually and numerically supports the argument against ceasing screening at age 69, uses data from federal public health sources (CDC, NCI SEER). The data clearly illustrate the progressive increase in the death rate for prostate cancer with advancing age.

Table 1: Prostate Cancer Death Rates by Age Group, United States

(Data sourced from CDC WONDER and NCI SEER 2).

The clinical unlikelihood of stopping screening at age 69 is underscored by the fact that the death rate continues to rise steeply after this point. The slowing of the historical decline in prostate cancer mortality, coupled with an increase in distant-stage diagnoses after 2011, may not be coincidental. These trends appear to be the long-term, population-level public health consequence of widespread disincentives to screening that were reinforced by changes in professional guidelines. The data reveal that the decision to deprioritize screening for certain age groups, particularly those who are at the highest risk, is a direct, causal factor in the increase of late-stage diagnoses and, subsequently, a contributor to the slowing of the mortality decline.

3.0 Cultural and Socioeconomic Influences on Preventive Care

3.1 Psychosocial Factors Shaping Men's Health Decisions

Men's lack of engagement with preventive care is shaped by deeply ingrained cultural ideals of stoicism and self-reliance (Walk-In Lab Resource Center 2025 8). This "power through" mindset, which equates seeking medical help with weakness or failure, creates a powerful psychological barrier to care, particularly for conditions that develop silently over time. This cultural conditioning leads to delayed help-seeking and the under-reporting of symptoms, a phenomenon so common that more than 40% of men reportedly do not seek medical care at all unless faced with a serious issue (Allstate Benefits 2022 10; Walk-In Lab Resource Center 2025 9). This disposition makes early detection nearly impossible, as men may be unwilling to discuss a seemingly minor concern until symptoms become severe enough to require intervention.

3.2 Socioeconomic and Structural Obstacles

Beyond cultural norms, practical, systemic barriers reinforce men's limited engagement. Traditional healthcare systems are often poorly configured to serve men's needs. For instance, clinic and office hours frequently conflict with typical work schedules and men may fear being perceived as "slacking off" to attend an appointment (UNC Health Lenoir 2020 11).

Financial pressures act as a significant deterrent. The rise of high-deductible health plans can make preventive care appear to be a discretionary expense rather than an essential service, creating a financial penalty for seeking a behavior that is already culturally charged and perceived as optional (KFF 2023 8; UNC Health Lenoir 2020 11). Studies suggest that individuals without health insurance are less likely to receive preventive care. Those with coverage may be deterred by out-of-pocket costs.10 This financial barrier is particularly acute for self-employed men who may face high premiums and a lack of comprehensive options.

The cultural and socioeconomic barriers are not independent problems; they are interwoven. The cultural norms lead men to avoid a healthcare system that is already poorly configured to serve them. The system, in turn, reinforces their ambivalence by presenting financial and practical obstacles. This demonstrates that addressing men's health is not simply a matter of "awareness" but requires a fundamental restructuring of the healthcare delivery model to actively engage men where they are, rather than expecting them to overcome multiple, compounding layers of systemic resistance.

3.3 The Influence of Provider and Institutional Practices

Institutional practices can compromise patient-centered care. Provider incentives may favor retaining care and treatment within a particular network, which could inadvertently skew patient choice toward in-house treatments rather than guiding men to a facility that have the expertise required for a procedure not offered in-house. Such practices undermine the concept of shared decision-making and reinforce skepticism among men who already perceive the healthcare system as uncertain or adversarial.

4.0 Policy and Legislative Disparities

4.1 The ACA and the Normalization of Women’s Preventive Care

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has been instrumental in creating a robust and standardized policy infrastructure for women’s health. Under the ACA, private health insurance plans are generally required to cover a wide range of women's preventive services without any consumer cost-sharing, including deductibles, co-payments, or co-insurance (HRSA 2024 12). The law recognizes the unique health needs of women across their lifespan and has provided specific guidelines for services like mammograms and cervical cancer screenings, including Pap tests (HRSA 2024 12). This legislative framework has significantly increased access to care, reduced out-of-pocket costs, and has been credited with normalizing a culture of consistent preventive check-ups for women (National Women's Law Center 2020 15).

4.2 A Policy Void for Men

In stark contrast, no similar federal mandate exists for prostate cancer screening under the ACA. While the ACA requires coverage for a variety of preventive services for adults, including screenings for conditions like hypertension, high cholesterol, and colorectal cancer, it does not universally include prostate cancer screening in the same manner as it does for breast and cervical cancer (Healthcare.gov 16). An exception is under the Medicare program, which has provided limited coverage for PSA tests for men over the age of 50 since 2000 (CMS 1999 18).

4.3 A Legislative Case Study: The State of Ohio

The state of Ohio provides a clear example of this policy disparity. The Ohio Revised Code, Sections 5164.08 and 3923.52, explicitly mandates comprehensive coverage for women's breast and cervical cancer screenings under both Medicaid and commercial insurance plans (Ohio Revised Code 2022 19). This legislation not only requires coverage for annual screening mammography but also for supplemental breast cancer screening, such as MRI or ultrasound, for women with dense breast tissue or an increased risk due to family history (Ohio Revised Code 2022 19).

No equivalent, comprehensive legislation exists in Ohio for prostate cancer screening. While a step forward, Ohio House Bill No. 33 (HB 33) is a proposed bill that only mandates coverage for "high-risk" men over the age of 40 (StateLawImpact.com 2023 21). This lack of a universal, proactive approach at the state level further underscores the legislative gap that contributes to men's limited engagement with preventive care.

The contrast between the policy frameworks reveals that public policy is not merely a reflection of existing cultural norms but an active, causal force that shapes them. The ACA and state-level mandates make women's preventive care a non-negotiable, financially painless, and routine aspect of healthcare. This policy-driven framework removes the financial and psychological burden of deciding whether to get screened, thereby creating a societal norm of proactive engagement. Conversely, the absence of similar mandates for men's health leaves the decision to the individual, subject to their cultural biases, financial situation, and varying insurance plans. This demonstrates that the policy gap is a key driver of the uncertainty and low engagement, reinforcing the cultural idea that prostate cancer screening is an optional, rather than an essential, component of care.

5.0 The Impact of Clinical Guidelines and Professional Response

5.1 The Breast Cancer Controversy: A Case Study in Professional and Public Mobilization

The USPSTF has a well-documented history of generating controversy with its recommendations. The 2009 USPSTF guidelines for breast cancer screening, which suggested that women in their forties should engage in "individualized decision-making" rather than receive routine mammograms, were met with a "vehemently negative outcry" from the public, specialists, and advocacy groups (JAMA Network Open 2025 23; PubMed Central 2022 24). This controversy stemmed from a fundamental conflict between the Task Force's methodology and the experience-driven perspective of specialty groups, who stressed the mortality benefits of mammograms and believed they outweighed the potential harms of overdiagnosis (PubMed Central 2022 24). The public’s rejection compelled the USPSTF to eventually revise its guidelines, recommending that all women begin screening at age 40, a notable reversal that demonstrated the influence of a mobilized patient population and professional community (JAMA Network Open 2025 23).

5.2 The Prostate Cancer Counterpoint: Relegated to Shared Decision-Making

This professional and public mobilization stands in stark contrast to the subdued response to the USPSTF's prostate cancer screening recommendations. In 2012, the Task Force issued a "D" grade, which recommends against the service, for all men (USPSTF 2012 25). Although the recommendation was updated to a "C" grade in 2018 for men aged 55 to 69, suggesting the decision should be an individual one, the task force maintained a "D" grade for men aged 70 and older, advising against screening entirely (USPSTF 2018 26). A "C" grade indicates that the USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that the net benefit of the service is insignificant. This means that a clinician and patient should make an individual decision about the service. A "D" grade indicates that the USPSTF concludes with moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits, and it therefore recommends against the service (PubMed Central 2022 24; USPSTF 2018 26). The stated rationale for these recommendations revolved around the potential for "overdiagnosis" and "overtreatment" practices, which can lead to relatively insignificant complications such as treatable incontinence and erectile dysfunction (USPSTF 2018 26).

The Task Force's move toward "shared decision-making" is intended to empower patients to weigh the benefits and harms with their clinician (USPSTF 2018 26). For women, who have a cultural and policy infrastructure that normalizes screening, this framework provides an additional layer of agency within an already-supportive system. In this context, the framework is a meaningful tool that empowers a proactively engaged patient base. However, men who lack this infrastructure and are culturally conditioned to avoid medical discussions, the burden of "shared decision-making" is disproportionate. It shifts the responsibility of navigating complex, conflicting evidence onto a population that is both systemically and culturally unprepared to do so.

Shared decision-making in prostate cancer screening presumes a foundational level of patient knowledge that is demonstrably lacking. The American Cancer Society’s 2024 survey found that 60% of men incorrectly believe the initial screening involves a rectal exam, and more than half are unaware that erectile dysfunction may be an early symptom of the disease. Nearly 40% were unfamiliar with family history affects screening eligibility, and 37% of unscreened men say they do not think they need testing yet despite prostate cancer being the second leading cause of cancer death in men. These findings reveal a widespread lack of awareness about both risk factors and screening protocols, which undermines the premise that men can meaningfully participate in nuanced medical decisions about testing (American Cancer Society 2024 27). When nearly half of men would be more likely to talk to a doctor if they simply knew screening starts with a blood test, it is clear that ignorance, not informed preference, is driving behavior. Shared decision-making in this context risks delaying detection and increasing late-stage diagnoses, especially when men are unaware that screening should begin before symptoms appear. Until foundational education gaps are addressed, expecting men to weigh complex medical options alongside their providers is not just premature; it is a public health liability.

The lack of public and professional outcry over the prostate cancer recommendations is not a sign of their widespread acceptance but rather a symptom of the very ambivalence and limited engagement this report seeks to explain. The breast cancer controversy illustrates that a proactive, engaged patient population is a prerequisite for "shared decision-making" to be a meaningful tool rather than a veiled form of abdication.

6.0 Conclusion and Areas for Future Consideration

The limited engagement of men with prostate cancer awareness is not an isolated behavioral issue but a product of an interconnected web of policy gaps, cultural influences, and counterintuitive clinical guidance. This report has demonstrated how a lack of federal and state mandates for universal, no-cost screening creates a legislative void that reinforces cultural norms of stoicism and self-reliance. This environment, in turn, makes the burden of "shared decision-making" a disproportionate and ineffective approach to care for a population ill-prepared to navigate the complexities of the healthcare system. The consequence is an increase in late-stage diagnoses and an unnecessary public health burden.

A fundamental paradigm shift is necessary to address this crisis.

Recommendations for Pragmatic Change:

Mandate insurance coverage of PSA screening for men comparable to women’s screening mandates. Legislation should require insurers (including state Medicaid and private plans) to cover PSA testing for men beginning at age 50 (or earlier for high-risk groups) with no or minimal cost-sharing and (American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network 2023 29; American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network 2025; American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network 2025).

Adjust screening guidelines to reflect age-related risk. National guidelines should extend routine screening beyond age 69 for healthy men, since mortality continues rising (American Cancer Society 2024 1; Cancer Research UK 2017-2019 4). This will ensure older men are not systematically screened out at an age of high risk.

Conduct targeted public education campaigns. Develop outreach programs in workplaces and communities to raise men’s awareness of prostate cancer risks and the importance of early detection. Messaging should be direct (avoiding euphemisms) and leverage trusted male figures to break down stigma about men’s health checks (American Cancer Society 2024 28).

Train providers to discuss prostate screening more proactively. Primary care and urology practices should routinely offer PSA screening discussions at age 50+, ensuring men know their options. Clinicians should emphasize that modern PSA protocols and follow-up (e.g., MRI, targeted biopsy) can reduce harms and improve outcomes.

Support research on men’s health behaviors. Fund studies to better understand the psychosocial and systemic barriers keeping men from screening, so that future interventions can be evidence-based and culturally appropriate.

For prostate cancer to be addressed with the seriousness it warrants, the approach to men's health must evolve from a reactive, risk-based posture to a universal, proactive, and comprehensive model of care. The ultimate goal is not merely to increase awareness but to dismantle the systemic and cultural barriers that have perpetuated a crisis of limited engagement for far too long.

References

Allstate Benefits. 2022. "Are Cultural Expectations Increasing Men's Health Risks?" Allstate Benefits News and Insights. Accessed September 21, 2025. http://www.allstate.com/allstate-benefits/news-and-insights/are-cultural-expectations-increasing-mens-health-risks.

American Cancer Society. 2024. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society. Accessed September 21, 2025. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2024-cancer-facts-figures.html.

American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. 2023. "Congress Introduces PSA Screening for HIM Act." American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network Newsroom. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://www.fightcancer.org/news/congress-introduces-psa-screening-him-act.

American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. 2025. "Prostate Cancer Survivors and Medical Leaders Call on Pennsylvania Lawmakers to Eliminate Barriers to Screening." American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network Newsroom. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://www.fightcancer.org/releases/cancer-survivors-and-medical-leaders-call-pennsylvania-lawmakers-eliminate-barriers.

American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. 2025. "Senate Introduces Bipartisan Legislation Aimed at Removing Cost Barriers to Prostate Cancer Screening." American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network Newsroom. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://www.fightcancer.org/releases/senate-introduces-bipartisan-legislation-aimed-removing-cost-barriers-prostate-cancer.

Cancer Research UK. 2017–2019. "Prostate Cancer Incidence Statistics." Cancer Statistics. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer/incidence.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 1999. "Prostate Cancer Screening Tests." Medicare Coverage Database. Accessed September 21, 2025.(http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=268).

Healthcare.gov. n.d. "Preventive Care Benefits for Adults." Accessed September 21, 2025. http://www.healthcare.gov/preventive-care-adults/.

Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). 2024. "Women's Preventive Services Guidelines." HRSA. Accessed September 21, 2025. http://www.hrsa.gov/womens-guidelines.

JAMA Network Open. 2025. "Is Less Frequent Screening the Reason for Lower Breast Cancer Rates?" HealthJournalism.org. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2025/01/is-less-frequent-screening-the-reason-for-lower-breast-cancer-rates/.

Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). 2023. "Trends in Individual Market Premiums." KFF. Accessed September 21, 2025. http://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/preventive-services-for-women-covered-by-private-health-plans-under-the-affordable-care-act/.

National Women's Law Center. 2020. "The Affordable Care Act: A Lifeline for Women and Families." Accessed September 21, 2025. https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ACA-2020-11-09-1.pdf.

Ohio Revised Code. 2022. "Sections 5164.08 and 3923.52." Ohio Legislature. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-revised-code/section-5164.08.

PubMed Central. 2022. "The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) 2009 Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening..." PubMed Central. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9576241/.

ResearchGate. 2024. "Ascertaining provider-level implicit bias in electronic health records with rules-based natural language processing: A pilot study in the case of prostate cancer." ResearchGate. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387533489_Ascertaining_provider-level_implicit_bias_in_electronic_health_records_with_rules-based_natural_language_processing_A_pilot_study_in_the_case_of_prostate_cancer.

StateLawImpact.com. 2023. "HB 33: Mandating Health Insurer Coverage for Preventative Prostate Cancer Screenings." StateLawImpact.com. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://statelawimpact.com/hb-33-mandating-health-insur- er-coverage-for-preventative-prostate-cancer-screenings/.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). 2012. "Screening for Prostate Cancer." USPSTF. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/how-did-the-uspstf-arrive-at-this-recommendation-/prostate-cancer-screening-2012.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). 2018. "Screening for Prostate Cancer: Recommendation Statement." JAMA, 319(18), 1901-1913. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prostate-cancer-screening.

UNC Health Lenoir. 2020. "Preventive Health for Men – Why It Matters." UNC Health Lenoir. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://www.unclenoir.org/news/2020/preventive-health-for-men--why-it-matters/.

Walk-In Lab Resource Center. 2025. "Medical Bias in Men's Healthcare." Walk-In Lab Resource Center. Accessed September 21, 2025. https://resources.walkinlab.com/mens-health/medical-bias-mens-health/.

info@crownsproject.org

1 (330) 554-0099

Subscribe for NEWSLETTER updates

© Copyright 2026 The Crowns Project. All rights reserved. The Crowns Project is a national 501 (c)(3) organization dedicated to providing educational resources, access, and assistance to aid in the early detection, treatment, and survival of prostate cancer

general inforomation